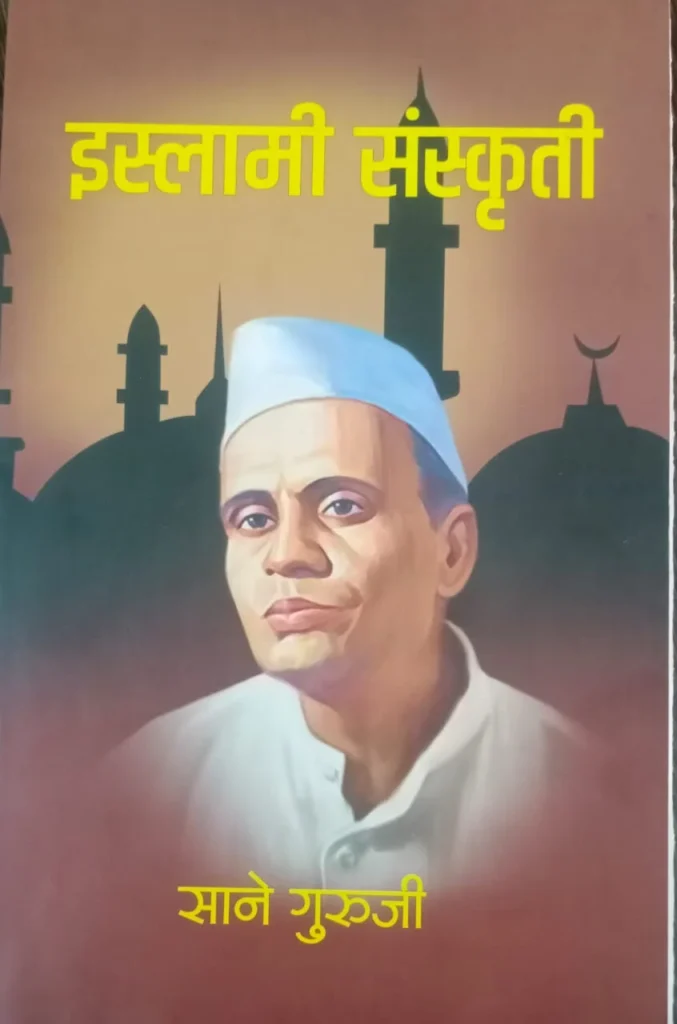

In an age of political division and communal suspicion, Sane Guruji’s Islami Sanskriti remains a luminous testament to interfaith empathy and moral vision. A devout Hindu, social reformer, Gandhian, and freedom fighter, Sane Guruji composed this work during his imprisonment in Dhulia Jail in 1931. Emerging from deep reflection and spiritual introspection, the book transcends sectarian boundaries to present Prophet Muhammad ﷺas a moral and spiritual reformer of universal relevance.

This article examines Guruji’s portrayal of the Prophet’s character – his compassion, justice, humility, forgiveness, and reformist zeal – as articulated through Islami Sanskriti. Through close reading and textual analysis, it argues that Guruji’s interpretation of Islam and its Prophet ﷺexemplifies an ethical universalism that resonates deeply with India’s pluralist spirit.

Composed amid the socio-political turbulence of pre-Independence India, Islami Sanskriti stands as a remarkable literary bridge between communities, shaped by Guruji’s reflections during incarceration. Published posthumously in 1964, it earned commendations from figures like Acharya Vinoba Bhave, who penned the Foreword, and Dr. Zakir Husain, the then Vice President of India, who lauded its contribution to communal harmony and moral education.

The Prophet ﷺas a World Reformer

For Guruji, Prophet Muhammad ﷺwas not merely a religious figure but a divine reformer and “radiant example of compassion, justice, and reform.” Through 32 chapters chronicling his life, Guruji portrays him as a world-transforming moral force, one who awakened humanity from its spiritual slumber. He vividly sketches pre-Islamic Arabia as a land “where the laws of God and humanity were trampled underfoot,” a society mired in “tribal conflicts, cycles of vengeance, and the horrific practice of burying infant girls alive.”

Into this darkness, he writes, “a new, thousand-petalled lotus blossomed in the form of Muhammad. Its fragrance spread across the world, and the suffering received its inexhaustible nectar” (Islami Sanskriti, p.38).

Highlighting episodes such as the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, the Conquest of Makkah, and the Constitution of Madinah, Guruji sees Islam as a movement of compassion. For him, the Prophet’s reforms were not mere religious injunctions but civilizational milestones.

Guruji situates Prophet Muhammad’s mission within a global moral crisis, noting that “the sacred flames kindled by Zoroaster, Moses, and Christ had gone out.” Humanity, he observes, was sunk in “ritualism, division, and moral decline.” The Prophet’s advent, therefore, was for all humankind: “The advent of Muhammad was not limited to Arabia; it was for the entire world.” (p.38)

Guruji enumerates the Prophet’s sweeping reforms: the abolition of female infanticide, promotion of widow remarriage, advocacy of women’s education, abolition of priestly monopolies, insistence on direct access to God, and the rejection of caste-like hierarchies. “Islam abolished the priestly class. In prayer, all are equal. Muhammad declared that before God, all are the same.” (p.53)

These measures, Guruji contends, “transformed Arabia into an ethical paradise.” He celebrates the Prophet ﷺas “a champion of equality and people’s rule, whose resounding voice in favour of popular governance shook kings and religious elites alike.”

For achieving his mission, Guruji writes: “Muhammad’s penance had been for the world. His unity with God was meant to save humanity; it was not for himself alone…. He faced all torment, suffering, and hardships without yielding. This great soul, standing for truth, did not bow before falsehood.” (p.50)

The Prophet of Forgiveness and Compassion

One of the most profound aspects of Guruji’s portrayal is his emphasis on the Prophet’s capacity for forgiveness. Despite facing persecution, exile, and personal attacks, the Prophet ﷺrepeatedly chose mercy:

“Even when opportunities for revenge arose, forgiveness was inherent in his nature. He found the sweetest sense of victory in forgiving his enemies.” (p.91)

Guruji recounts several episodes illustrating this mercy – the famine in Makkah, his forgiveness of those who sought to poison him, and the general amnesty after the Conquest of Makkah. When famine struck his former tormentors, “Muhammad stood up to help them… Thus, he repaid evil with love and forgiveness.” (p.98)

During the Conquest of Makkah, “After the victory of Makkah, he did not feel pride. His head was bowed. He said: ‘Today is a day of forgiveness.’” (p.98)

He notes further, “The concessions that Christians did not receive even from the rulers of their own faith were granted to them by Muhammad… In the history of the world, it stands as a unique example of tolerance.” (p.77)

For Guruji, this magnanimity defines the Prophet’s greatness: “Time and again, even in victory, Muhammad chose forgiveness.”

Islami Sanskriti presents the Prophet ﷺas a leader who upheld justice without malice, responding to enmity with generosity – qualities Guruji saw as the highest ideals of human conduct. He writes:

“He is all-powerful, an ocean of love, a boundless sea of compassion. This awakening – this spiritual rebirth – had Muhammad as its soul… From this fountain, the streams of eternal hope flowed…” (p.83)

The Prophet as Statesman and Humanist

Guruji devotes an entire chapter to the Constitution of Madinah, praising it as a pioneering multi-faith social contract:

“The Constitution of Madinah was a new social experiment, where Muslims, Christians, Jews, and original inhabitants all lived under a shared contract.” (p.116)

For him, this was an early model of secular governance grounded in divine accountability, resonant with India’s pluralistic ethos.

Sane Guruji finds in the Prophet’s military ethics a revolutionary moral code. Contrasted with the ancient practices of slaughter and plunder, Muhammad’s injunctions were profoundly humane:

“Do not deceive anyone. Do not betray. Keep your word. Do not harm small children. Do not destroy the homes of non-combatants… Do not cut down fruit trees.”

Such teachings, Guruji insists, turned war itself into an act of moral reform: “He declared a general amnesty… The entire army entered the city peacefully – no looting, no violence, no assault.”

Defender of Women and Human Dignity

In response to Orientalists’ criticisms of the Prophet’s marriages, Guruji offers a deeply empathetic defence:

“None of his marriages was for pleasure or lust. They were acts of care, protection, and social reform.” Vinoba Bhave echoes this sentiment: “Why do you consider Muhammad indulgent? If he were merely indulgent, the world could never have been won over by him.” (p.116)

For Guruji, the Prophet’s conjugal life reflected his humanity – a man of heart, duty, and compassion:

“Muhammad was solely a figure of mercy. He did good even to those who wronged him… His gentle and cultured heart is revealed through these stories.” (p.116)

Just as the charge of arrogance against him is false, so too is the accusation of lust. Labels of “licentiousness” were, Guruji asserts, “wrongly attached to him.”

A Transparent Life of Divine Simplicity

Guruji celebrates the historical clarity of the Prophet’s life:

“His life’s work is transparent – clearly visible to the world. There is no mysticism in it… No myths were spun around his personality.” (p.109)

In contrast to mythic heroism, Muhammad’s greatness lies in human realism – “a divine, magnificent life – full of sacrifice, forgiveness, courage, and spiritual inspiration.” (Chapter 31)

The Prophet’s moral legacy, he concludes, “is an unbroken flame of reason, compassion, and honesty.” (p.99)

Guruji situates Prophet Muhammad ﷺwithin a lineage of global moral and spiritual reformers:

“Buddha’s work was fulfilled by Ashoka, Christ’s by Constantine, Zoroaster’s by Urayzon, and Israel’s by Joshua. But Muhammad became the one who completed not only his own work in his lifetime but also the unfinished work of those who came before him.”

His religious mission, writes Guruji, “is vast, and his humanity is simple and straightforward.” To him, Muhammad ﷺappears as a modern sage – a reformer whose life, purpose, and work remain “transparent, complete, and luminously visible before the world.” (pp.109–110)

In the Prophet ﷺ, Guruji saw a life “devoted to the service of humanity and God.” His virtues – humility, compassion, patience, selflessness, generosity, and altruism – were deeply ingrained in his conduct. Those who met him, Guruji notes, “were inspired to love. People said, ‘We have never seen such a person before, nor shall we see one like him again!’” (p.125)

Sane Guruji’s Islami Sanskriti stands as a literary and moral monument to interfaith admiration. It is not merely a biography, but a devotional homage and ethical reflection on the life of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. Guruji’s portrayal transcends religious boundaries, presenting the Prophet ﷺas a beacon of universal ethics, justice, and love.

His closing words echo a timeless reverence:

“Salutations, a thousand salutations to that Great Soul!”

In these words, Sane Guruji, a Hindu saintly reformer, offered not only homage but also a vision of shared spirituality, where truth, compassion, and humility form the essence of divine civilization.

In this light, the Prophet’s life, as interpreted by Guruji, emerges not only as a historical exemplar but as a living ethical guide, offering hope, inspiration, and a blueprint for building a just, tolerant, and inclusive society today.