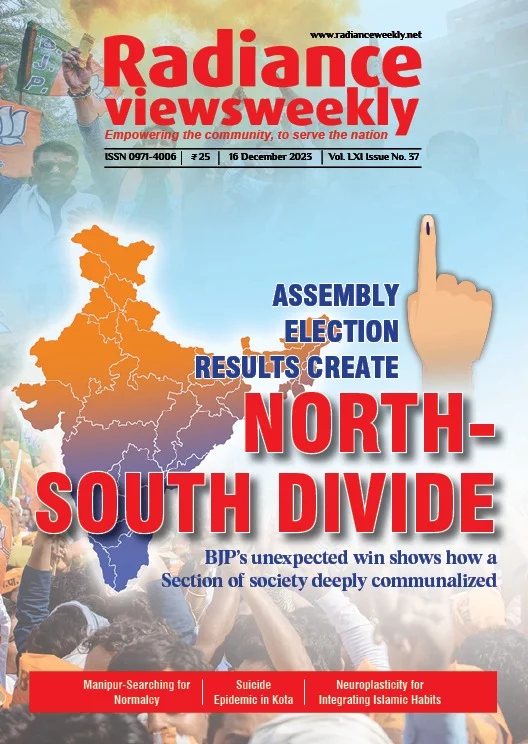

The surprising results of assembly elections in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Rajasthan ought to have shocked the Grand Old Party (Congress), which had remarkably overthrown the BJP’s rule in Karnataka just six months ago. The party’s lone consoling victory came from the southern state of Telangana, where it overthrew Bharat Rashtra Samithi’s ten-year rule.

The ruling BJP’s victory defied the majority of pre-election forecasts, which had indicated that the Congress would win at least three of the five states headed for polls. The result once again proved that, in spite of numerous difficulties, a sizable portion of the populace in North India continues to adhere to communalism and bigotry. The outcome also showed the Congress’s incapacity to mount a credible opposition in a bipolar contest with BJP as the party tried to play the “soft Hindutva card” in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh while its incumbent government didn’t check hatemongers in Rajasthan, fearing to lose Hindu votes.

However, it seemed the saffron party’s triumph in the northern states eclipsed Congress’s win in the southern states. With a resounding absolute majority, the BJP won back power for a fifth term in Madhya Pradesh and ousted the Congress governments in Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan.

Many political observers were surprised by the election results, which went against their expectations. Even prior to the elections, there was a general perception that Congress would easily win in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, and as the campaign came to a close, there was optimism regarding Congress’ victory in Telangana. Given the 25-year history of the state’s alternating political parties in government, Rajasthan was perceived as a close contest. The results also show a North-South divide in Indian politics. The BJP is largely confined to North India, while Congress in the south.

The Congress governments in Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan executed a comprehensive welfare program and governed with competence, but in these elections, there was no distinct political platform that could oppose the BJP’s tactics.

Madhya Pradesh

In Madhya Pradesh, the Congress was hoping for a rerun of the 2018 assembly elections, in which the party managed to unseat the ruling BJP, only to lose power in 2020 as a number of its MLAs defected to BJP. Ultimately, it appears the Congress was unable to match the BJP’s numbers, despite Kamal Nath, the leader of the party, expecting to exact revenge for the downfall of his brief government. The party won 118 seats, while the BJP garnered 109 seats in the 230-member assembly in 2018. In 2013, BJP’s tally was 163.

To win over voters, Congress chief Kamal Nath was largely dependent on a soft-Hindutva campaign. Many analysts said Kamal Nath had lost the fight right then and there. He did not spare any effort to implement a more moderate version of Hindutva than the party had in any state before. Kamal Nath made no mistake about his support for Hinduism, from commemorating the building of Ram Temple in Ayodhya to promoting himself as a devoted follower of Hanuman Bhakt.

Then, months before the polls, Congress teamed up with the right-wing Bajrang Sena, which had previously conducted a protracted campaign for BJP. By promising them improved land rights, the party also attempted to win over disgruntled temple priests.

Luring traditional BJP vote banks, like pujaris, was always going to be a challenge. It is clear that the Congress’s plan was unsuccessful, and it might have even aided the BJP by highlighting their strong Hindutva in contrast. For example, in Dewas, one of the main locations where the Congress tried its pujari-outreach, the BJP candidate got a huge lead of over 25,000 votes.

Furthermore, the BJP never truly put Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan forward as a candidate for chief minister; Kamal Nath has been the face of the Congress campaign since the very beginning. Nath obviously failed to mobilize voters on local issues, even though the party mostly focused on them – something that has benefited it in states like Karnataka and Himachal Pradesh. Furthermore, the former chief minister lacks strong regional backing outside of Chhindwara, from which he has been repeatedly elected as an MP, as well as a devoted caste-based vote bank.

To top it all, Nath operated primarily as a one-man operation, excluding most of the cadre and Congress strategists active in other states, such as Sunil Kanugolu, who was essential to the party’s success.

Another mistake Congress made was not accommodating INDIA bloc partner, the Samajwadi Party.SP chief Akhilesh Yadav had demanded an alliance with the Congress and asked the latter to accommodate it with six seats, but Nath refused any alliance with the SP. Following the refusal, Yadav criticized Congress, accusing it of being selfish. SP fielded 69 candidates, which have dented Congress’ prospects in the districts bordering Uttar Pradesh.

In this central Indian state, the Congress doesn’t have the most powerful organization. This can be explained by the fact that, with the exception of the 15 months it lacked power following the 2018 elections, the BJP has ruled continuously since 2003. The party’s cadre is therefore deeply ingrained and challenging to challenge. In 2020, the Congress organization suffered even more when Scindia defected to the BJP, taking with him a number of his 22 MLAs and a cadre that was loyal to him.

Chhattisgarh

In neighboring Chhattisgarh, the BJP won 54 seats out of a 90-member assembly. While the ruling Congress won 35 seats. One seat was won by the GondvanaGantantra Party (GGP).

The state is another example where the party imitated soft Hindutva which badly proved counterproductive. According to observers, the Congress also faced significant dissatisfaction from tribal and minority communities for what they see as its “soft Hindutva” ideology.

Speaking with Radiance, Arun Pannalal,National President,Sarv Adi Dal, said in 2018, Congress had 72 seats with the full support of the Christian community.

“This time there was no support from the Christian community, hence it was reduced to 35 seats. Maybe Congress will act wisely in the future. The murder of Christian priests, attacks on churches, and riots against Christians in the hope of garnering Hindu votes have cost Congress dearly. Soft Hindutva has backfired,” Pannalal observed.

It is also said that the party lost out primarily to urban voters. A political analyst said, “Urban voters also help build the image that the Congress failed to capture.”

Rajasthan

Rajasthan maintains its ‘riwaaj’ (tradition) of selecting a new government every five years. With 115 seats, the BJP defeated the Congress with 69 seats. Although the Congress has not won, this is the most seats the party has managed to secure in a loss in the previous six elections. With 21 seats, it suffered its worst loss in 2013. In 2018, the situation was nearly identical, as the BJP secured 73 seats while the Congress secured 100 seats.

Despite the departing Chief Minister’s people-centric narratives, which even the BJP was forced to adopt, the Congress has lost. The internal conflict in Congress was one of the factors that was being discussed everywhere in the state. The display of infighting between Ashok Gehlot and Sachin Pilot was evident. Pilot was seen as acting like the ‘opposition’ until a few months before the polls.

Whether or not the Gujjars voted for the Congress is the main issue, even though the intricacies of the caste divisions need to be analyzed. A community that accounted for about 7% of the total vote had previously sided with the Congress because it believed Pilot would become the next chief minister. The Gujjar voters were clearly dissatisfied with the Congress this time around after their hopes were dashed. They make an impact in at least 30 seats. The party failed to retain the Gujjar voter base intact. There was also a great deal of resentment among other minority voters, as crimes against Adivasis and Dalits rose at an average annual rate of 22% between 2018 and 2022.

Divisive campaign

A recent study by the Washington-based research group Hindutva Watch states that in the first half of 2023, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan tied for third place among Indian states in terms of anti-Muslim hate speech. By bringing up issues like the building of Ram Mandir and fabricating stories around state-reported communal incidents, the BJP infused the election narrative with its tried-and-tested Hindutva plank. The BJP used the lynching of Junaid-Nasir, the killing of Kanhaiya Lal in Udaipur over the Nupur Sharma controversy, and the alleged illegal trade of cows in border regions as major campaign issues. Following the Danish Ali controversy, BJP MP Ramesh Bidhuri was nominated as the election in-charge of Sachin Pilot’s Tonk, a predominantly Muslim constituency. This move was perceived as an attempt to divide the Congress leader’s base of support, which includes both Hindu and Gujjar votes.

Furthermore, the BJP fielded rabid rabble-rousers such as Baba Balak Nath from Tijara, Pratap Puri Maharaj from Pokran, and Balmukund Acharya from Hawa Mahal. According to a survey, Baba Balak Nath is the second most popular person to be the chief minister of the state and is in the shoes of UP CM Adityanath.

Similar to other states, the BJP’s top leadership, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, once again focused on raising the profile of sensitive issues while carpet-bombing the electoral field with rallies and road shows as the campaign neared its conclusion.

Telangana

Anti-incumbency sentiment, voter fatigue, and discontent among young voters were the main causes of BRS’s dismal performance in the election.

The perception of BRS leaders’ inaccessibility added to the growing anti-incumbency sentiments, even in spite of the party’s extensive grassroots network and welfare programs, as well as the towering image of BRS supremo and Chief Minister K Chandrasekhar Rao.

Since the state’s creation in 2014, the BRS has controlled Telangana politics, and since 2001, it has also maintained a sizable presence in the politically divided state of Andhra Pradesh.

At first, the BJP was seen as the primary opponent of BRS; however, after the Congress gained strength following the Karnataka elections, things changed.

Allegations of an unspoken agreement between BRS and BJP undermined the party, causing anti-establishment votes to converge in favor of the Congress. This was especially true in relation to the Delhi excise policy case involving CM Rao’s daughter Kavitha.

In this election, emotional factors didn’t play a major role as they did in previous elections, where sentiments for separate statehood were crucial.

The perception was further aggravated by the opposition’s projection of what they referred to as the BRS family rule in the state. Its decision to renominate the majority of the sitting MLAs didn’t produce the expected outcomes either. Six members of the departing KCR cabinet were soundly defeated by Congress and BJP candidates in elections, indicating a strong anti-incumbency sentiment among Telangana voters.

With a campaign focused on change and a catchphrase that effectively connected with voters, Congress ran an assertive campaign: “marpukavali, Congress ravali” (There should be change, Congress should come).

Congress won 64 seats in the 119-member assembly, while the BRS tally was reduced to 39 seats. All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) retained its seven assembly seats, and the BJP improved its tally from one seat to eight. CPI won one seat.

In the race for the Jubilee Hills Assembly seat, BRS sitting MLA Maganti Gopinath defeated Congress candidate and former India cricket captain Mohammad Azharuddin.

BRS sitting MLA Maganti Gopinath defeated Congress candidate and former India cricket captain Mohammad Azharuddin in the contest for the Jubilee Hills Assembly seat. BJP’s T Raja Singh won the Goshamahal assembly seat, defeating BRS candidate Nand Kishore Vyas, who is notorious for anti-Muslim statements and was suspended by the party. The BJP’s other controversial MP and ex-state chief, Bandi Sanjay Kumar, lost to BRS rival Gangula Kamalakar Reddy by 3,163 votes. The BJP’s three MPs lost the election. Nizamabad MP D Arvind lost to his BRS rival Kalvakuntla Sanjay by over 10,000 votes, and SoyamBapurao lost to BRS’ Anil Jadav.

Muslim representation further shrinks

In Chhattisgarh, lone Muslim MLA Mohammad Akbar lost to the BJP in the Kawardha seat. While in Madhya Pradesh, Congress’ Arif Masood and Atif Arif Aqueel retained their Bhopal Central and Bhopal North seats, respectively. Another Muslim leader from the Congress, Nafees Mansha, who had contested from AIMIM after being denied a ticket by the grand old party, however, lost from Burhanpur. Mansha garnered 33,853 votes, which was higher than the victory margin of BJP’s Archana Chitnis against her nearest rival from the Congress, Thakur Surendra Singh. In Rajasthan, several sitting Muslim MLAs lost elections to the BJP candidates.

The bottom line is that the Congress-led INDIA alliance should not lose heart, taking a cue from the recently concluded World Cup of Cricket, which didn’t determine the eventual champion by winning the semifinal. These results of the elections do not necessarily guarantee the outcome of the general elections. According to senior journalist Vinod Agnihotri, “The caste census issue has not failed. If Congress and other social justice forces raise this issue continuously, it will become a core issue in Indian politics. VP Singh brought Mandal, but in 1991, Janta Dal lost Loksabha polls miserably, except in Bihar. But the issue remained alive, and the course of politics has changed.”