While awarding a life sentence to a woman for smothering to death her two minor daughters in 2018 and terming it a “cold-blooded murder”, a Delhi court stated in its order: “No doubt, the mother is always seen as a saviour because of her nurturing role and perceived sacrifice and for that reason, society intends to idolise motherhood, expecting women to be selfless, nurturing and emotionally resilient.”

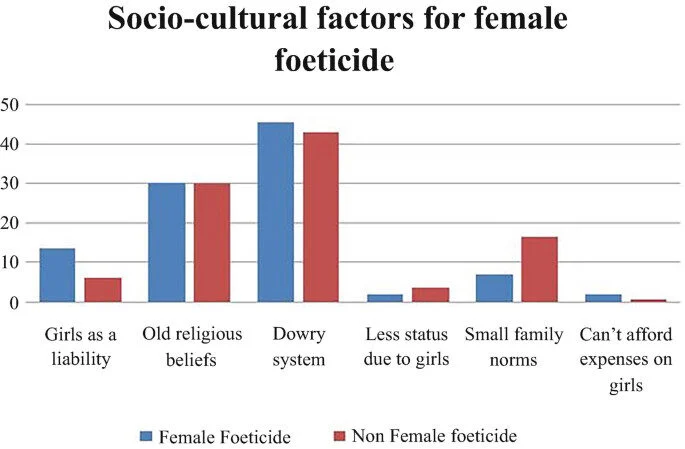

The issue of female foeticide in India encapsulates a profound social crisis that challenges the fundamental human right to existence for women. Rooted in a complex interplay of cultural norms, economic pressures, and systemic gender biases, this practice has led to alarming gender imbalances within various communities. Legislative efforts, such as the PCPNDT Act, have aimed to combat this issue; however, deep-seated patriarchal attitudes persist and continue to fuel the preference for male offspring. Critical analyses reveal how socio-economic factors, including the dowry system and perceptions of girls as liabilities, contribute significantly to the perpetuation of this practice (Dewangan Set al.). Visualisation through data, such as the compelling insights depicted in, accentuates the prevailing social attitudes that dignify male life over female. Addressing female foeticide necessitates a multifaceted approach aimed at dismantling these entrenched societal beliefs and transforming cultural perspectives towards gender equity.

The phenomenon of female foeticide in India exemplifies a deeply entrenched societal issue shaped by cultural preferences for male offspring. This gender bias is especially pronounced in specific states where traditional beliefs reinforce the notion that daughters are economic burdens due to practices such as the dowry system, while sons are seen as bearers of family legacy and economic support. Extensive research underscores how these societal norms impact the female-to-male birth ratio, a tragic consequence of women’s devaluation in society. Notably, studies reveal a significant divergence in sex ratios attributable to prenatal sex selection practices, with an estimated 0.48 million girls aborted annually from 1995 to 2005, showcasing the surge in selective abortions where families fail to achieve their desired number of sons (Bhalotra S et al.). Visual representations, like the bar graph illustrating socio-cultural contributors to female foeticide, provide a compelling backdrop for understanding the pervasive attitudes that sustain this critical issue.

Causes of Female Foeticide

The phenomenon of female foeticide in India is significantly driven by cultural and socio-economic factors that prioritise sons over daughters. This systemic son preference can be traced back to deep-rooted patriarchal norms, where males are viewed as financial assets and carriers of family lineage, while females are often seen as liabilities due to the associated dowry burdens. Economic pressures further exacerbate this dichotomy, leading families to adopt female foeticide as a means of mitigating perceived financial strain. The impact of policies and societal attitudes reflect an alarming trend, effectively shaping public discourse around the issue.

According to recent analyses, “The root cause of female foeticide in India is a complex web of social, cultural, and economic factors. At its core lies the deeply entrenched preference for sons, which stems from patriarchal norms that value males over females. This preference is further reinforced by economic considerations, where sons are seen as financial assets and daughters as liabilities due to practices like dowry.” (Tulsi Patel).

Visualisations, such as the bar graph indicating socio-cultural factors, clearly illustrate the influence of these attitudes, underscoring an urgent need for comprehensive reform. Moreover, the government’s initiatives, outlined in studies like those by (Purewalet al.) and (ActionAid et al.), highlight the importance of framing these issues within broader discursive contexts to effectively address the daughter deficit.

Socio-cultural factors contributing to the preference for male children

The preference for male children in India is deeply rooted in socio-cultural attitudes, which are reinforced by age-old traditions and economic considerations. A predominant factor driving this preference is the belief that boys serve as financial assets for families, particularly due to the burdens associated with dowries and marriage expenses for daughters. The perception of girls as liabilities, as depicted in the analysis from Tulsi Patel, highlights societal norms that equate male offspring with economic advantage. Furthermore, the decline in sex ratios, particularly in states like Rajasthan, illustrates the impact of male literacy on the persistence of son preference, as indicated in (Singariyaet al.). Despite legislative frameworks aimed at curbing female foeticide, such as the PCPNDT Act, these entrenched cultural beliefs continue to prevail, creating a challenging landscape for gender equality in India (Papalkaret al.). Addressing these socio-cultural factors is essential for fostering a more balanced and equitable society.

Consequences of Female Foeticide

The practice of female foeticide has engendered profound socio-cultural consequences in India, fundamentally altering gender dynamics within society. One of the most alarming outcomes is the stark gender imbalance, with reports indicating regions hosting as few as 750 girls for every 1,000 boys, which exacerbates issues like violence against women and human trafficking. This demographic distortion has repercussions that extend beyond individual families, triggering a crisis of marriageable women and perpetuating social instability, as highlighted in statistical analyses.Furthermore, the ingrained societal preference for sons leads to persistent discrimination against females, reinforcing patriarchal norms that undermine women’s status. Grounded in primary research from Haryana, it becomes evident that entrenched cultural values continue to fuel this preference, illustrating the slow progression of social norms.Such dynamics ultimately foster a culture where women face heightened vulnerability, with dire implications for societal cohesion. The imagery of gender imbalance, reflecting the socio-cultural factors at play, underscores the urgency of addressing these longstanding attitudes.

Impact on gender ratio and societal implications

The persistent practice of female foeticide in India has resulted in a significant gender imbalance, disrupting societal norms and challenging the foundational values of community stability and integrity. With a declining female-to-male birth ratio, regions such as Haryana exemplify the dire consequences of entrenched son preference and the societal valuation of women. These conditions not only exacerbate gender discrimination but also foster a culture where women are seen as liabilities, further entrenching economic and social disparities (Anderson S et al.).

Additionally, campaigns aimed at combating female foeticide often hover within a disciplinary framework, creating a paradox where saving the girl child intersects with punitive measures against those who perpetuate gender-selective practices (Purewalet al.). The interplay between policy responses and deeply rooted socio-cultural beliefs underscores a precarious situation that challenges the very fabric of Indian society, signalling urgent need for comprehensive change. The bar graph illustrating socio-cultural factors contributing to female foeticide poignantly depicts the greater influence of traditional norms, thereby reinforcing the critical discourse surrounding this issue.

In conclusion, addressing female foeticide in India necessitates an integrative approach that combines legal initiatives and cultural transformation. Despite the establishment of laws such as the PCPNDT Act aimed at curbing gender-based discrimination, the persistence of deeply entrenched socio-cultural norms continues to undermine these efforts. The statistical analysis presented in the research demonstrated the correlation between factors like son preference and economic burdens, underscoring the necessity for comprehensive educational campaigns to alter societal perceptions regarding gender.

Prominent discussions reveal that without addressing the underlying gender biases perpetuated by practices such as the dowry system, legislative measures alone will be insufficient. Moreover, a successful strategy must involve collaborative efforts by government entities and civil society organisations to promote awareness and create supportive frameworks for girls. Hence, a multifaceted strategy is crucial for eradicating female foeticide and fostering a more equitable society.

To effectively combat female foeticide in India, it is crucial to synthesise the key points surrounding the socio-economic dynamics that perpetuate this grave issue. As articulated, ingrained cultural preferences for male offspring, combined with economic pressures related to dowry, significantly contribute to the alarming practice of female foeticide. Interventions must, therefore, not only encompass legislative measures but also embrace educational campaigns that shift societal views toward gender equity. Research underscores the necessity of both carrot and stick approaches, with financial incentives promoting daughter empowerment coupled with stringent legal frameworks against discrimination. Furthermore, sociocultural factors, such as the perception of girls as liabilities and the dowry system’s influence, highlight the need for targeted educational initiatives. Tackling these intertwined issues will require collaborative efforts across various societal sectors, thereby facilitating a more profound transformation in attitudes toward female children.

BetiBachao,BetiPadhao, initiative by the government is an appreciable step. Yet one has to wonder that do these steps suffice or a largescale movement has to be started in this regard?

[The writer is Associate Professor, Department of Arabic, MANUU, Hyderabad. Email: drsamtabish@gmail.com]