India is now in a completely new situation in terms of economic challenges. They demand creative solutions that might require a re-look at how we treat family as an economic unit, writes Arshad Shaikh

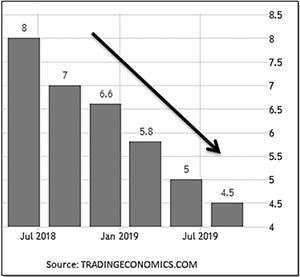

India’s GDP growth has been on a downward spiral for many years. The July-September figures of 4.5% growth are the sixth consecutive quarter that has seen falling growth rate. The year on year (YoY) percentage growth of 8 core industries is down to negative 5.2%. Rail freight traffic is negative 8.1% (YoY); Major Port Cargo Traffic is negative 5.4% (YoY) while Bank Credit to Industry has reduced from a high of 6.9% (YoY growth) in March 2019 to 2.8% in October 2019.

Exports show negative 4.6% (YoY) growth and many other key economic indicators like Petroleum Products Consumption, Domestic Commercial Vehicles Sales, Domestic Passenger Vehicles Sales, Domestic Tractor Sales, and Two-Wheeler Sales – showing negative growth. Hence, it is not surprising that Fitch Ratings cut its growth forecast from 5.6% to 4.6% for the 2019-20 fiscal. Others like Moodys, Asia Development Bank, and RBI have projections of 4.9%, 5.1% and 5% respectively for FY 2019-20. With this deceleration in growth, reaching the target of a $5 trillion economy seems a pipedream for India.

Twin Balance Sheet Challenge

Former Chief Economic Advisor of India (CEA), Arvind Subramanian recently opined that India’s economy was in “ICU” and was facing a “Great Slowdown”. He had repeatedly highlighted India’s Twin Balance Sheet (TBS) problem way back in 2014, namely the debt accumulated by private companies and the Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) of banks. In a new paper co-authored with former IMF India Office Chief, Josh Felman – Arvind states that the TBS problem, which he terms as the Second Wave of Balance Sheet crisis, has bloated into a new form with the addition of the NBFC crisis and freezing of the real estate sector. He writes, “Since the Global Financial Crisis, India’s long-term growth has slowed as the two engines propelling rapid growth – investment and exports-sputtered. Today, the other engine consumption has also stalled. As a result, growth has plummeted precipitously over the past few quarters.”

The former CEA points out that the “interest-growth” differential, which is the difference between the corporate cost of borrowing and GDP growth, is more than 4% points. This implies that the interest on debt is accumulating at a faster rate than the revenues that companies are able to generate through sales and production. This stress reduces growth, which increases the stress further leading to a vicious cycle that is grinding down our economy.

Global vs Domestic slowdown

Jehangir Aziz, Head – Emerging Market Economies, JP Morgan, in an interview to Bloomberg Quint spelt out some very interesting reasons for the state of India’s economy. According to Aziz, we have always believed that all our problems on growth are supply side issues as there is always domestic demand. That may not be the case. In fact, we just grew riding the wave of globalisation as any emerging economy would and now that globalisation has encountered financial meltdowns and global trade issues, India is facing low growth that is proving to be extremely sticky. Therefore, it is the slowdown in external demand that is applying the brakes on India’s economy. However, we continue to believe that there exists perpetual domestic demand and so we apply all solutions towards supply side like corporate tax cuts and other monetary and fiscal tools.

The JP Morgan economist asserted, “I would say that just like any other emerging market economy, barring perhaps China, all these emerging market economies are having the same problem. They were addicted to globalisation; they hitched their entire growth model to that bandwagon that served them extremely well for the last 10-15 years. Unfortunately, that game is over more or less. They are struggling, almost every one of them, struggling to put together the structural reforms that would turn around and change the drivers of growth. The search for the alternative engine growth that is missing in almost every emerging market and India is not an exception. I think, that is where the problem lies. Emerging market economies cannot continue to believe that as long as we keep our body and soul together for another year. Somehow miraculously the global growth is going to pick up, global trade is going to pick up and we will be once again back to the old days of 8-9 per cent growth”.

Working on the demand side

A solution that can address the domestic demand problem is reduction in GST but not a permanent one, as it will seriously jeopardise the already precarious fiscal position. Instead, there should be a two-year window for reduced GST that will encourage spending and improve aggregate demand. M Umer Chapra writes in “Islam and the Economic Challenge” about how we can improve aggregate demand without incurring its negative externalities. Quoting Michael Harrington –”Twilight of Capitalism” and Paul Baran & Paul Sweezy – “Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Economic and Social Order”, the book says: “There is a growing realization now that “the large-scale ‘modem’ industrialization strategies of the previous decade generally had failed to solve the problems of global underdevelopment and poverty.”

Studies conducted in a number of countries by the Michigan State University and host country scholars have clearly indicated the rich contribution that SMEs can make to employment and income, they create new jobs not only directly but also indirectly by expanding incomes, demand for goods and services. tools and raw materials, and exports. They are labour-intensive and require less capital and less foreign exchange. They rely primarily on personal savings, retained earnings, and need much less access to credit from governments and financial institutions compared with largescale industries. They invent new products, revive lost skills and help economies move into new kinds of work. They can be more widely disbursed and thus help maintain the link between a person’ s place of work and his home which largescale industries and hectic urbanisation have severed to the detriment of social health. Moreover, they are at least as efficient as largescale industries.

India is now in a completely new situation in terms of economic challenges. They demand creative solutions that might require a re-look at how we treat family as an economic unit. It requires both courage and patience.